Zombie fires are ravaging peatlands in France

Sep 30

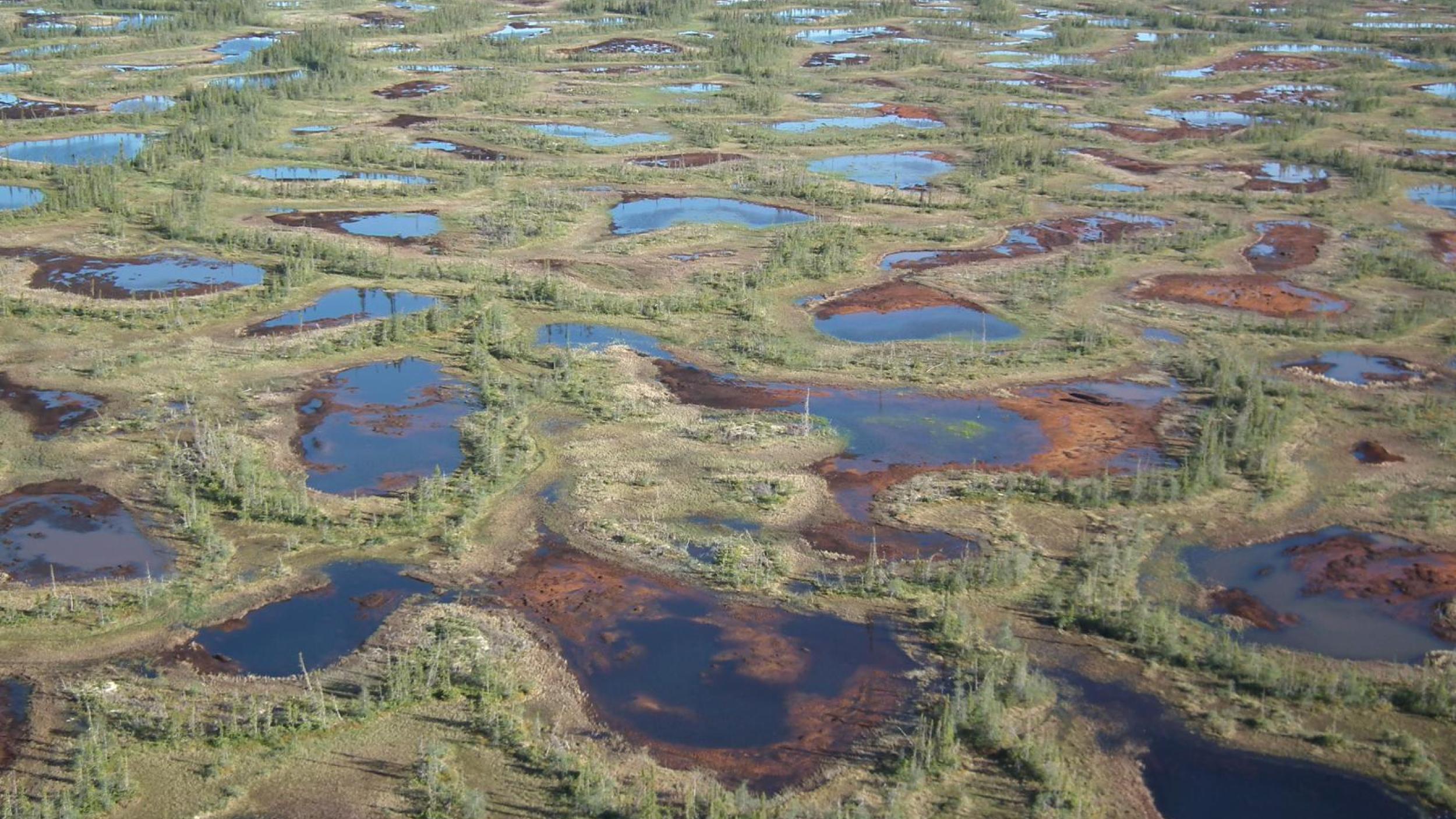

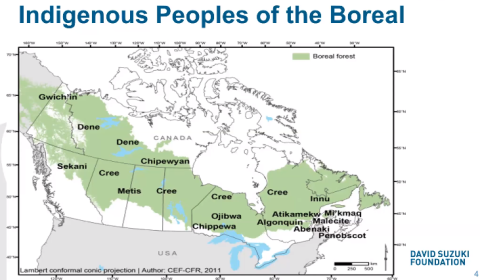

While much attention has been given to tropical peatlands, Canada’s Boreal and Arctic peatlands and their extraordinary landscapes have long been overlooked and have only begun to gain global attention recently. Not only they are home to a vast range of biodiversity including charismatic megafauna such as caribou, polar bear, wolves, moose, peatlands play a vital role as migratory stop-overs, breeding, and staging grounds for hundreds of species of birds. They are also part of traditional territories of Indigenous people whorely on peatlands for their social, community, cultural, and economic values and play a key role in their protection for a very long time (Source: WCS, 2020)

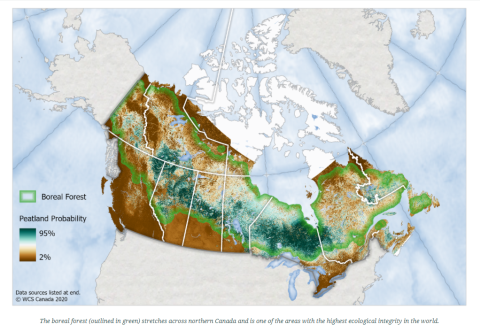

While 32 per cent of the peatland global cover worldwide can be found in the northern parts of North America, Canada retains the largest continuous peatland areas (Source: WCS, 2020). With peatlands covering around 12% of the total land area, Canada holds the title of one of the world’s largest carbon stores. Their extent, the carbon they hold and the many ecosystem services they provide, highlight why Canadian peatlands must be protected, for biodiversity, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and for the planet and its people.

Did you know? 1m2 of peatlands in Northern Canada holds 5 times the amount of carbon as 1m2 of Amazonian tropical forest (Source: WCS, 2020)

Although they are incredibly important ecosystems, they are increasingly under threat from a variety of disturbances including mining, oil and gas development, road construction and hydro-electricity development as well as natural disturbances such as wildfire.

Despite the growing momentum to mobilize governments, international organizations, the private sector, and academia in a targeted effort to protect peatlands, there is still a need for more countries, policy makers to become aware of the urgency of action to prevent the loss of peatland carbon stock to fires, degradation through drainage, or disturbance and agricultural conversion. Furthermore, extending formal protection of arctic and boreal peatlands is extremely important, yet has been overlooked area in climate change adaptation and mitigation dialogues.

The Canadian government, with the support of indigenous organizations conservation initiatives, have taken great measures to protect their boreal forests by establishing additional protected areas.

In order to inform policy, we need better peatlands maps and better information on land cover changes through time. These should be based on the best and latest available data and modelling of future scenarios. To achieve this, interdisciplinary and inter-sectoral collaboration is needed to answer some key questions to fill science and data gaps: Where are peatlands in Canada and how are they changing? How much carbon is locked in these peatlands? To answer these questions, a better understanding of complex interactions between the hydrology, ecology and biogeochemistry of peatlands is needed.

As a multi-partnership initiative, the Global Peatland Initiative (GPI) organized, together with the Scott J. Davidson and Maria Strack from the University of Waterloo’s Water Institute a series of three workshops entitled ‘Canada’s Peatlands: Towards A National Assessment’. Since its creation, the Global Peatlands Initiative has promoted collaboration between all relevant stakeholders and networks as the only way to bring science to the global dialogues and inform policies for peatlands conservation, restoration, and sustainable management. As such, the three workshops were designed to stimulate knowledge exchange between Canadian researchers and NGOs, industry partners, the private sector, and government representatives with the overarching aim to enable the strengthening of the multidisciplinary and multisectoral Canadian peatlands network.

Some of the discussions have focused on the integration of Indigenous people in conservation policy design. The David Suzuki Foundation has supported the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas by supporting the process with assistance with funding proposals, sharing stories and tools, and bringing together First Nations and other policy makers together. They, among others, highlighted the need to integrate Indigenous groups and build on the connection between their knowledge and experiences on climate change and environment, and the work of scientists.

“The Boreal is not just a place on the map. It is also a home to First Nations and Indigenous peoples. These Nations rely on the boreal for spiritual and cultural and physical sustenance.” Rachel Plotkin from the David Suzuki Foundation expressed emphasizing the important role they play as environmental stewards.

Other discussions revolved around the knowledge products that have already been developed, or are in the process of launching. For example. Ducks Unlimited Canada have been focusing on wetland/peatland mapping methodologies as presented by Kevin Smith and have conducted wetland inventories across Canada. Similarly, Natural Resources Canada and their Canadian Model for Peatlands (CaMP) which aims to modelling Canadian peatland greenhouse gas emissions at a national scale, presented by Kara Webster. The CaMP will be the data source used to model peatland emissions to be included in the CBM-CFS3 inputs to the national inventory.

Similarly, other discussions from the three-part workshop focused-on restoration. Paul Short, President of the Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association (CSPMA) shared knowledge on peatland restoration targets. As an example, CSPMA created a peatlands restoration guide, explaining in details the eight steps to successfully restore a peatland: http://peatmoss.com/responsible-production/peatland-restoration/.

Throughout the sessions, participants raised the need to improve current peatlands inventories, including through a harmonization and standardization of data collection, methodologies, measurements and techniques and through the exchange and combination of datasets.

This problem was further raised by Danielle Cobbaert, from Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP). Danielle presented the Alberta Merged Wetlands Inventory, an inventory based on the best available data, from 35 different inventories conducted across the province and which aims at guiding the government for land use planning decisions and give recommendations on wetland conservation and restoration areas, wetland management priorities and regional planning scenarios. However, AEP highlighted that large data gaps still remain for some regions and they have experienced a variation in details and accuracy. To overcome this problem, the Alberta is publishing its Alberta Wetland Mapping Standards and Guidelines is in the final steps of being published. The Alberta Wetland Mapping Standards and Guidelines aim to provide methodological consistency and efficiency in gathering results, in order to provide higher quality inventories. This may provide an opportunity for other provinces and territories to use similar methods to harmonize data collection.

A working group was also established by the GPI and Prof Mark Reed (SRUC) to discuss further fine-tuning to the core outcome sets. These include methods and indicators for peatlands research, by establishing common research questions, data and approaches to strengthen and harmonize efforts on peatland research. This will allow complementarity with other findings and integration into other datasets (see also our previous article on that work).

Did you know? In 10 and 15 years after restoration peatlands move from carbon source to become carbon sinks (Nugent et al., 2019).

With more than 150 participants from academia, government, private sector, and NGOs from more than seven different provinces and territories, the discussions were rich and exchanges successful. These workshops are a first and vital step towards the establishment of a peatlands inventory in Canada. As requested by the UNEA-4 Resolution on the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Peatlands, work is underway by the GPI on the Global Peatlands Assessment (GPA) – aiming to establish the state of the world’s peatlands, acting as a baseline against which to catalyse action. The GPA will help partners establish and jointly communicate the status and value of peatlands, outlining hot spots for urgent action, and include emerging opportunities to restore and protect them. It will incorporate best practice in policy, and tools for conservation, restoration, and sustainable management. This will involve building on the best available data on peatland state, trends and pressures – while illustrating the opportunity for a triple win for the climate, people and the planet. The GPA hopes to inspire collaboration, positive action by showcasing successful and promising approaches to peatland conservation, restoration and sustainable management that co-exist with prosperous and healthy lives.

“Globally, we have so much uncertainty in our stock estimates, in particular in northern peatlands and that’s why this assessment and this collaboration are so exciting” said Justina Ray of WCS Canada.

Together with the attendees of the workshops, the Global Peatlands Initiative will establish working groups on a range of different topics in 2021 including one dedicated to Canadian peatlands. The network established during the three-part workshop will be essential in coordinating the contents of the Canadian chapter.

“Protecting Canada’s peatlands will be key for the government to meet their carbon emission reductions targets. Not only will their protection help curb climate change, it will also protect the unique biodiversity they hold and through the vital ecosystem services they provide, secure the livelihoods of the people livingg on them.” says Dianna Kopansky, Coordinator of the Global Peatlands Initiative.

For more information, please contact Dianna Kopansky (dianna.kopansky@un.org) and Scott J. Davidson (s7davidson@uwaterloo.ca).

Further resources:

Sep 30

Sep 30

Aug 31